Mining the West for 'likes' is fueling permanent closures.

A new form of mining is sweeping the West without any ethics or governance to account for externalities, and it's leading to widespread loss of access to public lands.

Posts on The Fleeting West are written and posted quickly and are often edited for clarity and quality later. For the best experience, see the copy on the website for the most up-to-date version.

It's road trip season, and guess where everybody is headed? … "Out West!" as they say.

As social media outlets, such as YouTube and Instagram, bubble with posts about new places our influencers and content creators "discovered," overuse and misuse reach levels the lands of the West haven't ever seen. What's the harm, you say? Well, let's get into that.

In the grander scheme, the internet created new avenues for conveying information about every single thing imaginable, instantaneously, and without the barriers to entry that previously required some intensive personal, social, and financial investment to overcome.

You don't have to be good enough at something to write a book about it and then actually get it published anymore. Or get recognized by a major TV network to do a video, or be rich enough to make your own video series on media that people would actually buy. Anyone with a computerized device with a camera can share high-definition information with mass audiences instantaneously — even if that information is damaging, harmful, or just plain idiotic.

Barriers to sharing information are now effectively gone, which I think we can all agree has done an immense amount of good, while we're still working to create culture around how to handle the bad.

In the past, to find locations to spend time wandering around open land, you had to cultivate intensive skills to do it well, and you had to accept a certain level of risk given there were no resortified rescue services to come pull you out of a bad situation. Not to mention there were no cell phones, so a CB radio and an understanding of how to use it was likely the only way to get any kind of message out when stranded and injured. Even then, you might only be lucky to catch a signal to actually get help in a reasonable period of time.

You had to know your horse or vehicle, your personal limits, how to navigate, and have self-rescue and -recovery skills — or a willingness to suffer and, hey, maybe even die.

The paradigm shift the internet continues to facilitate has been rapid and intensive when it comes to exposure of public lands due to the total removal of barriers to broadcast information about locations, what’s out there, and how to get there.

Photographs are no longer taken on film and only sharable as far as your arm could reach, or by the number of prints you could afford to make. Images now drive people to places from far and wide without any more effort than snapping an image with your camera-phone, pushing a couple buttons, and sharing with every single "follower" you might have on your social media account.

Then, with enough likes and interest, the post is now available to a mass audience to be fed to people you've never met and would never meet in the first place. The reach of social media will even reach people you would despise if you did meet them, completely without your need to know or ability to connect that dot.

There is no “social media ethic” or “tourist ethic”

Public lands are a bit of an oddity because they're not all managed the same way, and not all share the same infrastructure. Posting places to social media now instantaneously exposes locations that have no infrastructure, signage, or controls in place to handle suddenly and vastly increased visitation. Since there is no "social media ethic" or "tourist ethic" in existence that we have broadly acculturated to, there are no social curbs or policy reasons for limiting the sharing of these places with the whole-internet audience.

What the public land agencies in the West do when these places are exposed, then inevitably abused1, then flagged by other visitors to the area land managers is to ... close them. Or to add museum-style infrastructure to control the onslaught and natural impacts caused by crowds.

And they're closing them in mass, at a rate we've never seen in the West. Access to public lands are closing by thousands of miles per year in the interior West, while few/no new access points are being opened, except for tourist-grade recreational hiking opportunities in tourist infrastructured areas. Utah is the most visible battleground right now where lobbyist- and federally-driven closures are rampant2, while other places are more quietly being consumed by tourist-centered land grabs with new National Monuments, Wilderness Act-designations3, and preparatory road closures to ready for the next phases of exclusion.

Areas with their pre-urbanized condition intact once went unnoticed by anyone but resource extraction companies, livestock operations, or the experienced local who wandered out as far as they could during their free time. Now, these places are largely abandoned by extractive industries due to shifts in where these extracted resources come from and shifting environmental attitudes that outsource resource extraction to other states and countries instead. The metal for ski poles and snowshoes still comes from somewhere4 …

Hilariously, 100% of the roads and paths that exposed most of canyon country and most of the mountainous regions of the West to the modern tourist and influencer to go discover5 and broadcast were entirely made by and for resource exploration and extraction. Resource exploration and extraction includes mining, oil and gas harvesting, livestock grazing, earth quarries, logging, and a few others. And it's no coincidence that everything in Utah was named after Hell or the Devil — the land was regarded before recent times as having no value whatsoever, except for raw materials.

But mining established routes into these places and opened them to others who eventually found them sublime enough to visit them over and over again. Cultural memory knows you wouldn’t find a New Jersyian alive in the deserts of the Southwest until the last couple decades when the area was popularized and marketed as a destination of acquired taste and made-safe adventure.

The areas that have not been turned into tourist beacons in the form of National Monuments and National Parks were left to the local people for the most part, until social media facilitated their exposure and broadcast to pretty much everyone.

It's no coincidence that the interior Western states are all peppered with National Parks and Monuments. These were all installed by the federal government as a function of boosterism6 to drive people into these spaces to help make use of previously inhospitable land. And to hold the land from anyone else who might have already been there ... another topic for a later post.

Differentiating the three land management agencies for different kinds of public land users

The tourist-centered land management designations are entirely built to drive and manage mass visitation by paying customers.

The National Park Service (NPS) and National Monuments (usually operated by BLM7 or USFS and sometimes in collaboration with NPS) arise where there is some feature that now needs more attention due to increased visitation and all that comes with — from traffic jams to vandalism to looting to human waste piling up on every surface.

The rest of Western public lands, which accounts for most of the land area, is largely uninfrastructured, unmaintained, and doesn't reliably have such things as bathrooms, running water, guard-railed designated routes, road grading, and other such luxuries provided to keep non-local and urban tourists happy, clean, and safe. These areas are managed by the BLM and USFS.

The difference between the agencies that manage different areas of public lands is crucial to understand when hashing out the ethics of posting locations on social media.

Posting locations on social media and YouTube have direct impacts that differ by the location being posted

When someone posts a video about "the best kept secret in Oregon!" on YouTube, they expose the place to all of their followers, then anyone who might be fed their video by YouTube's algorithm for as long as the video is up on the server. The number of views on some of the most preposterous and poser-created8 content can easily hit the hundreds to millions of views over time.

Looking at the number of potential views and considering what happens when even a fraction of a percent of people are inspired to go to the place they saw online, it becomes clear that the content-maker has kicked off an exponential growth of visitation for this place that was once only visible to a few locals, on maps, and off the beaten common tourist path9.

The impact becomes interesting when you realize that this place would have only remained visible to people who have acculturated to methods of self-supported travel that also happen to simultaneously build ethics and skills around how to use the land in such a way that leaves no trace. The most abused places I've ever seen were exposed online, exposed to a whole-internet audience, and then snowballed to the point of total annihilation.

If that seems far fetched, take a moment to search the internet for the Conundrum Hot Springs near Aspen, Colorado, and the words “human waste,” where rangers and volunteers had to close the location for a period and backpacked out entire trash bags full with dozens of pounds of human fecal matter left directly on the ground around the natural hot spring. Now, it’s a denuded, frequented, abused, and infrastructured site that is only visited by a very specific kind of tourist that shares no common ground with those who came before mass exposure to the whole internet.

Fecal coliform bacteria started growing in waters around the springs because the novice users who never learned backcountry ethics and skills didn't even clean themselves before getting in the springs in mass numbers. Then, they posted their exploits to social media, and the exponential visitation snowball gained energy and speed. Now, it’s a high-travel zone and requires a permit to access legally — no longer wild and free.

The impacts of social media on public lands is an externality10 that is only starting to become visible to more people. For those of us who have been traveling these spaces for generations, the problem has been visible for a long time. Only now, after a few years of early social media influencers exposing these places and getting some time in the saddle, even they are starting to change their behaviors in light of the impacts.

The shift in content creator behaviors always starts with idiotic click-baited titles about "the best kept secrets discovered in [insert area name]!", then they progress to more mild content once they get comment-lambasted by local people for effectively destroying their home spaces by exposing to an entirely new and novice audience online. Social media users who post locations are even starting to show signs that they’re noticing that the places they could once get some solitude are now bustling encampments of social media-inspired followers.

Their tone changes, then they stop talking about places ... if they actually care about the places they’re exposing, that is. Unfortunately, very few genuinely do.

Posting locations outside of National Parks is a decision made by one person for all other users and the land

When you look at what's happening across the interior West, and in these spaces, you might realize we're in a state of total overrun and overuse by an entirely new group of people. Spaces that were once unknown, unrecognized, and only known as "flyover country" due to the prior fads that kept people wanting to live the comfortable city life are now "destination country."

People from all over the country are flooding the entire interior West to get a piece of what they're seeing on social media, including YouTube11. They are here to do what they saw someone else do. They're here to see the place they saw on that Instagram or YouTube post. They're here to discover that best kept secret! They're here to explore, to conquer, and to be in awe of what their favorite influencer showed them. But they're here to do it under the belief that they’re doing it the same as that picture of rugged individualism they saw someone else acting out online ...

In that, those inspired by and following social media posts are merely highly programmable consumers. They're not here because of an authentic reason deep-down that they've been working to cultivate for years, decades, or even generations. They're here to picture themselves as something in a place they already saw online, but they want their picture in that place so they can show other people what they think they discovered.

These individuals are followers of social media miners, who are followers of other social media prospectors, who followed yet another and another ... and somewhere at the root of that endless tree, they are followers of some unsuspecting Pollyanna local who posted their photos, maps, and routes online without yet understanding what would cascade from their simple little post about their favorite hiking, fishing, or camping spot.

When you put information out for the whole world, the whole world might just show up and claim the space as their own. Sounds familiar.

Every single post on social media is an advertisement - even the ones of your breakfast

Trip reports, guidebooks, personal posts to Facebook, Instagram, MySpace ... you name it ... are all advertisements of a place to as large of an audience as the user and platform can gather. Trail-finding apps are intended to expose places by people who have visited to anyone who downloaded the app. The audience of these apps are able to "shop" for their next hike, climb, ride, or drive based on how epic the photos of the scenery are, or how great the description of the trail, road, or fishing hole is.

Map reading is apparently no longer a prerequisite skill to finding places well outside your skill-set if you look at how apps and social media have changed the game. Just decide any day that you want to go try out hiking, and you can shop all of the places by the photo posted. You can pick by what state you want to go to, how many miles you want to hike before you get to that epic Instagrammable shot, where you can fly your camera drone for the most insane and click-worthy image ... no prior skills needed other than want and the impetus to put on the new hiking costume and go. It’s like Tinder12 for open lands … swipe right for the pretty ones, left on the ugly ones. Intuitively, the pretty ones always see the most traffic.

We don't have a word for what that is yet — but it's something like scenery capitalism13. Oddly, since the internet is free and these apps and platforms for sharing information are all only funded by ad revenue and not the users directly, maybe it's more like scenery socialism? …

No barriers to entry, all you have to do is 'want' and you shall receive. No more studying maps, developing skills, being able to self recover, orient yourself, or wandering places near you to develop a deep appreciation for your surroundings ... just download the app, start shopping, buy new hiking shoes and start going.

The new ability to shop for places to go by scenery you've already seen without having to learn anything first, including the ethics that inherently come with a lifetime of investment in practices, is creating new and unrecognized externalities.

The elephant in the room is that essentially all of the social media content makers selling out the West for likes and ad revenue are not from the region. Every single one that the algorithms have forced on me are transplants or tourists who used other social media posts to locate and visit places. Inherently, they do not behave like the local people do in these places, they don't treat them like they are in a sacred space, and they don't care who they invite in to follow and copy their motions.

It's full-bore tragedy-of-the-commons at 1,000 megabits per second. The impacts of hedonistic tourists creating outdoor pseudo-adventure porn out of public spaces, and following others who broadcast before them create compounding exposures to places that aren't ready to support the weight of the careless urbanized public.

Once the issue is recognized by more people, it will become clear that social media is creating externalities on public lands that will almost definitely shutter and reshape the entire public lands model as we know it.

Tourist boosterism is the latest iteration of extractive industries of the West where we mine the land for ‘likes’ and more tourists

Externalities on public lands stemming from social media are directly akin to the early days of the mining industry in the West where there was no regard for the place, and absolutely zero accountability by users for damages that would eventually be recognized.

Instead of mining for materials deep in the ground with intensive investment needed to get to the ground, then deep into it, we're facing mining that happens entirely on the surface. Prospects are now scenic vistas for influencers to expose to ad-revenue-generating audiences, rather than seams of gold, silver, uranium, or other valuable materials.

If you don't think those seeking scenery capital for their social media accounts are creating externalities, take a gander at Arches National Park entry on any Thursday through Sunday. The local people of the region are now basically barred from visiting due to mile long lines of cars packed three wide with queues to get in.

Once-quiet backroads and trails in Colorado that could be visited by local people in solitude are now parked and camped solid with thousands of vehicles creating tourist tent cities. Backcountry areas that were previously just lines on a map and known to only a few locals now have so much fecal matter sitting atop the ground and toilet paper and Clif Bar wrappers scattered about, they're unvisitable.

Backroads in Utah that once cleaved the common tourist by not being knowable without skills, risk, local knowledge, and investment of time and skin now have careless bypasses on every obstacle that require basic skills and a stock 4WD to pass through. All fuel for the land agencies, lobbyists, and politicians to drive mass closures.

The consumption of public lands is at a fever pitch right now, and the inspiration to go capitalize on ones own social media feed is well past red-line. Talk to any of the local people in Boise, Idaho, Bozeman, Montana, Estes Park, Colorado, and Moab, Utah, right now, and I suspect that all but the most Pollyanna14 and dull of them will tell you that what they're experiencing is total annihilation at the hands of mass influxes of tourists and invasive tourists (aka. transplants) that don't have a single care or clue what they're doing.

And the more grand and sublime the place is, the more likely it is to be consumed rapidly and in large numbers.

The glaring oddity in all of this is that even our most museum-centered land management agency, the NPS, is even overloaded and overwhelmed at this point. Thanks to the outdoor industrial complex, companies like REI have helped to drive people into spaces they would otherwise have no interest in being to help expand their industry and sell more outdoor tchotchkes and costume pieces.

Many of the West's national parks now have lotteries to enter, queues to control the flow of people due to being at maximum capacity, and heavy permit requirements for visiting anything outside of the usual lined and signed tourist sidewalks.

Social media posts about places are inauthentic and are by those who want to be seen

For those of us watching as this drama unfolds in our home landscapes, it is clear that most to all of the social media posts about these places are inauthentic.

The people making these posts aren't here because they're interested in traveling quietly, and participating in the more minimalist lifestyles that many of us in the West incidentally popularized. They're here to create an advertisement of themselves in these places doing things they've seen done, and they're looking to do these things with the most click-worthy tchotchkes that make them look like they're real doers as interpreted by their novice audiences.

There's a deep lack of authenticity in any of the content being created, whether of a young woman in her yoga costume doing Warrior Pose on a cliff edge, or an urban bro setting up his rooftop tent on a mountain top while wearing his mountain costume, or a Johnny Jetta type pretending to "backcountry ski" out of bounds at the ski resort. The content is fake, the intent is fake, but the externalities are deep, unrecognized, and unaccounted for in their receipt of unprecedented social and financial revenues from extorting these places and the people who have inhabited and traveled these spaces for generations.

It's interesting to have been a young adult when social media started to roll out, then watch the progression of social media in creating new and different cultural effects. What's even more interesting is to watch social media snowball into creating immense, clearly identifiable, and deep externalities in spaces that were previously not known at all, and simply grouped as "flyover country" — as in the words of many people from urbanized areas of the country I've listened to, "there's nothing out there." How times have changed ...

Social media posts about places outside National Parks are signed death warrants that only the local people will be forced to endure

The decision of an individual to post a location to social media is a decision to create an advertisement for the place, as every single thing posted to social media is an advertisement. Every single post on social media advertises ones own identity, a restaurant, art, land, an activity, a product, and so on — whether users realize it or not. They're advertising something to as wide of an audience as they can possibly get, sometimes in exchange for ad revenue from the social media platform.

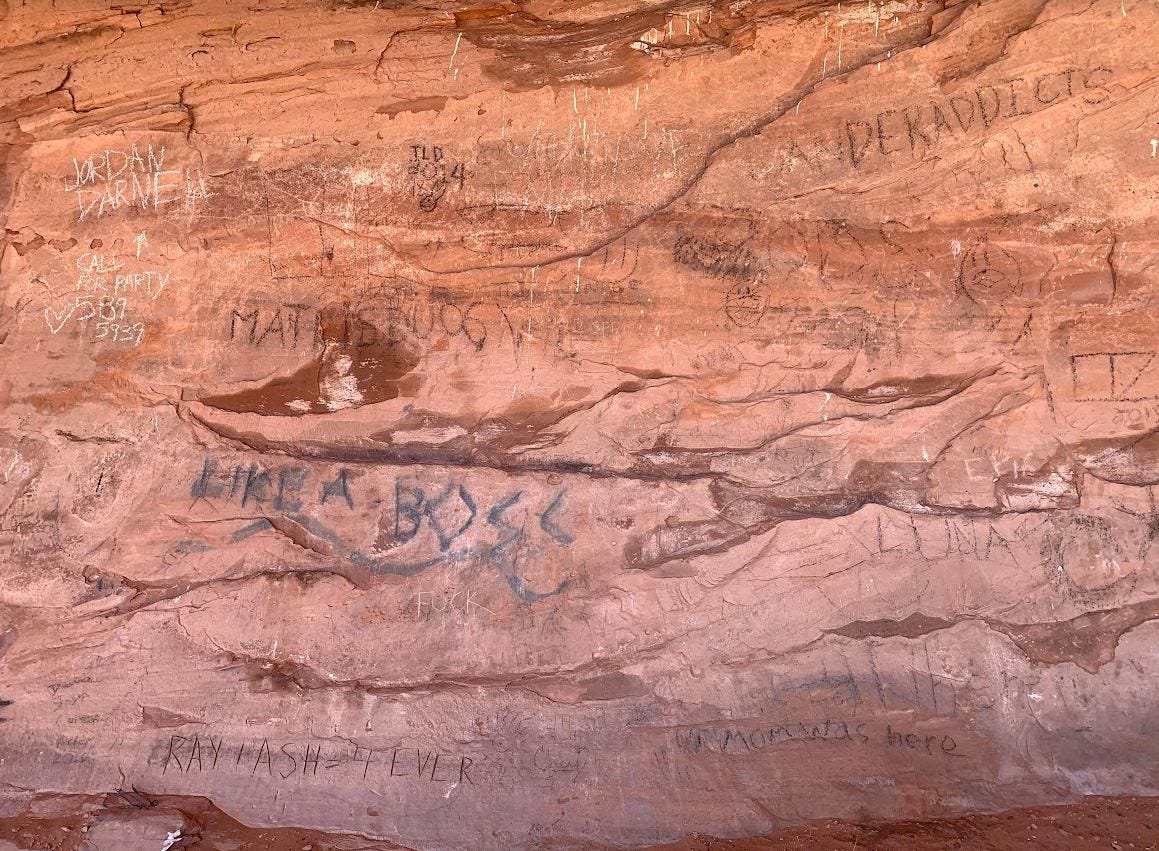

The problem is that advertisements of public lands are for spaces that aren't a product, and for which we know from all prior experience, do not fare well when visited in mass without some kind of infrastructure to guide and curb the masses. If in doubt of that fact, take a look at every space that has been exposed on social media and then look at what's happened within years after initial exposure. Damage to the land, area, character, including everything from litter to ecological damage, to vandalism ensue — in all cases.

And, sure, the damages of mass numbers of people is only relative to the perception of other people. But it appears that every single time a place is exposed and then inevitably misused, it either causes public outcry that the place needs to be cleaned up, resulting in infrastructure being added, or it gets closed down due to lack of resources to manage it. I've watched this happen repeatedly and endlessly over the decades. Someone posts a location with some epic-looking imagery, and boom — death warrant — the place is crawling with people within a couple of years, inevitably followed by political action and either new infrastructure our outright closure.

The decision to post a location online is a political one. It's a decision for all of the people who tracked these places through time to have the place exposed to a whole-internet audience, with all ethics-inducing barriers to entry foregone. It's a decision to sign a death sentence for the place and all of the local people who have wandered in these places for generations. It's a decision to create an advertisement for the place for a whole audience, none of which you know or care about. Posting a location to social media is an entirely self-serving decision to create an externality that everyone but the person posting it (it appears) will endure for the foreseeable future.

The only form of mining that doesn't stop, doesn't have any curbs or regulations, and creates immense externalities spanning economy, culture, and environment is mining places for likes and ad-revenue on social media. We need an ethic around the posting of locations, or at least a way to account for mass influxes of followers and the damage they inherently do to the places that are not yet infrastructured for mass tourist traffic. The only form of mining that never leaves once it arrives is rote tourism for entirely external audiences participating in scenery capitalism. Lord knows the local people aren’t impressed by that influencer-tourist’s discovery of that trail, road, or fishing hole in our backyard …

The Fleeting West is written by a rooted Westerner embedded with generations of experience on public lands, and observing rapid and rampant political damage driven entirely by social media scenery capitalists.

Footnotes and Citations

When I say “abused,” I don’t just mean used heavily by considerate users. I mean human waste being left on the ground, toilet paper strewn everywhere, trash being stuffed behind and around rocks and trees, garbage being left, potato chip cans being placed on tree branches, glass bottles and cans being thrown into fire pits, constructions of things like makeshift toilets, eye-bolts screwed into trees to hang tarps, hatchets being used to hack up every tree in the vicinity, and so on … we’re not talking footprints here, we’re talking the actions of depraved tourist imbeciles. I don’t use the word lightly.

Closures across the West are rampant right now and go largely unnoticed. More about that here:

It’s important to understand the difference between ‘wilderness’ (places that have a feeling of wildness) and capital-W-wilderness. Most use the two interchangeably, but they aren’t. The Wilderness Act prevents use in an area to all mechanised travel, including bicycles. All motor vehicles are excluded, bicycles, electric bicycles, ATVs, airplanes, helicopters, and so on — you may hike, and hike with livestock and that’s it. Capital-W-wilderness is a political boundary and creates intensive exclusions of current and historic uses. Albeit an important tool for use in some cases.

Hiking, snowshoeing, and skiing are petroleum sports … more about that here:

Notice, the modern tourist or influencer are always preloaded with the tourist starter pack of language about what they’re doing … They’re always on an “adventure” and are “discovering” or showing you a “best-kept secret.” That’s a post in and of itself, and I will use the word “discover” throughout this post as something of a joke to be exposed in detail later.

Boosterism is the historic practice of promoting a place to drive people to it for the purpose of driving economic activity in places that previously had little to none. The word is directly tied to Manifest Destiny in the West, of which both terms have been abandoned in the age of social media and mass migrations to the West in the years after about 1950. Social media posts and people moving to the interior West in mass numbers are participating in boosterism and Manifest Destiny without realizing it.

BLM - Bureau of Land Management, a separate federal agency from the National Park Service (NPS) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS).

Read more about the impact of geotags, trip reports, so-called “adventure apps” here:

Externality - An action that affects other people without being accounted for in costs of the good or service. It’s a primary function of the “Tragedy of the Commons,” in which shared areas are more abused due to lack of clear ownership and acculturated ethics to treating spaces as ones own. An example is a geologic hot spring that users then pollute with fecal matter by not caring for the place as if having value.

I mention YouTube separately because most do not seem to recognize it as being social media in the same way as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are. YouTube is the king of social media.

Tinder - the popular online dating app where you “swipe” on photos of people to decide if you might want to talk to them or not. Now we can do that with public lands!

Scenery capitalism or adventure capitalism — more about that here:

Pollyanna - as in, excessively optimistic and cheerful to the point of being delusional and missing the harm happening right in front of them.