Novice users are changing the face of public lands in the West

The explosion of interest in the outdoors during the pandemic exposed wounds in the ethics of public lands use, and came with some ugly new negative impacts.

In the new American discourse, having a lifetime of outdoors experience is now being called a “privilege.” Funny, because most of the country once looked down on it (loudly, I might add), as something the poor, unclean, and “granola” did for reasons unknown. And most of us did it because it’s what was available and it was accessible without much in the way of financial resources (of which many of us had none). It didn’t pass the wealthy or aspirational urbanite test for a worthy way to spend one’s time when there were the … finer things in life … to experience, like expensive boats and time spent in America’s big cities.

The ramp-up in interest in the outdoors was long and varied, and then came the pandemic, which significantly changed the trajectory of interest. Companies, like REI, have been marketing and promoting outdoor use for a long time to help drive sales of merchandise. Kudos to them, I guess – mission accomplished - and what timing! But something happened during the pandemic that caused the once increasing trends of outdoor use to go through the roof like a rocket – of which we felt especially hard here in the interior West.

In states like Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Montana, Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada (sorry, California … you didn’t make the list because you’re totally and utterly screwed and have been for decades), we all experienced what felt like a nuclear increase in population growth, almost overnight. The pandemic kicked off, and there have been times in Colorado where I’m driving in a pack of cars and I’m the only Colorado plate. The interior West got hammered by a tsunami-wave of people looking to “get closer to nature” and because “the mountains were calling” (their words, not mine.)

The wave of new people showing up to buy houses, build houses, rent houses, live in vans, and so on, is unlike anything we’ve experienced in the West since the gold rush. We have something like 20 offers per house for sale in Boulder County per one home (that’s a 20:1 ratio of people to homes, ahem…) And they all came to use our trails, learn to camp, and to get their hands on some of that “Rocky Mountain High.”

Since the State Demographer in Colorado is always one Census away from totally useless, they have absolutely no idea how many people migrated to the state during the pandemic. Since that’s a provable statement, I’m going to guess; I think Colorado added 500,000 to 1,000,000 people since the start of the pandemic.

The reason this is interesting is that they all appear to be from the following states (estimated by looking at license plates): California, Texas, New York, New Jersey, Missouri, Kansas, and Florida.

I’m going to call that a pretty informed guess, but I don’t dare put numbers behind it.

There’s a common thread among all of those states that helps to indicate who these people are and what they know – they’re all likely from urbanized areas, and all but the Californians, likely have absolutely no exposure to the outdoors in any way beyond infrastructured areas. Yep, I’m generalizing, and from experience with people from all of these areas, my generalization is likely provably on the button.

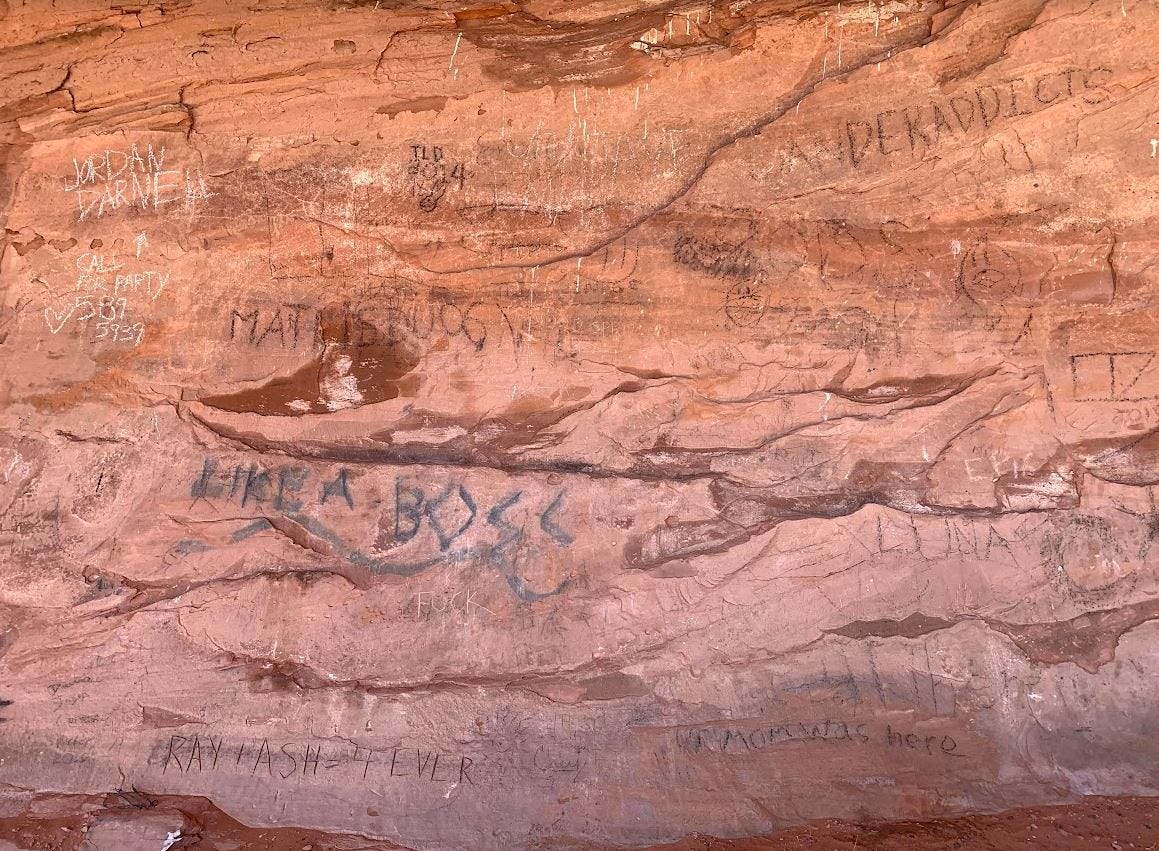

Whether these suppositions about how many people and where they’re from are even close to right, there is one huge observable change in Colorado and the West that can be used to derive support for these otherwise, unscientific observations; The way public lands are being used in the West has changed rapidly and dramatically.

Experienced users of public lands will tell you how to do things right – and most of those things focus on knowing where you are, going prepared, how to handle bodily functions the right way, to pick up your trash, and how to leave no trace. And almost all of those norms are … completely out the door.

Deriving a takeaway message from that, it appears that most of the rapid uptick in land use appears to be driven by novice users.

Summing up some of the novice behaviors…

Dispersed camping appears to be happening in the wrong places and with the wrong practices

I’ve seen fire hearths built in the middle of forest roads (because someone just stopped and camped there, in the middle of the road). Fire hearths in non-campground areas are getting filled with nonsense trash that wouldn’t normally be found. Campers are driving into a place they found on a trip report / YouTube, finding people, then camping right next to them. Yeah, just happened to my parents – they were camping away from crowds, and some guy came and camped 20 yards from them, ignoring the hundreds of thousands of other acres they could camp on. Are these people scared to camp alone?

Novices’ first instinct is to photograph, video, and share their location online for all of their friends to see, and to make sure strangers see them there as well

It’s always very obvious when you find a person online who really just got started in using the outdoors – fresh out’the City. They always want to share with everyone where they are, and make sure the image of where they are is shown. They have to tell EVERYONE about this great place they discovered. Which is interesting – It’s a very political decision to share a place online, because who are you to tell everyone about this trail that the locals built and may not want to find droves of posers in later. The way people picture themselves in a place tells a lot about how they regard that place, and their skill level in being there.

Nobody seems to be carrying maps, or know how to read them - the number of lost people in need of help is astounding

A few years ago, I had a trip upended by a novice transplant from West Virginia who had gotten separated from his friend. Long story short, he didn’t know where his friend was and continued to tell me about his preparations – he pulled out his phone and “prepared” meant taking screenshots from Instagram on this climbing route up a remote peak in Colorado that he and his friend went to climb to … “test out their new rubber” … as in, they bought some new approach shoes, and went to test them out by climbing a peak they found on Instagram. Well, that story is long and incredibly stupid, but when I pulled out my map of the area and asked where his friend was, he told me that he couldn’t really tell me because he doesn’t really read maps well.

And what I’ve found is that almost none of the people navigating these places now carry or understand maps. They all appear to come with printed or screen-shotted trip reports and trail apps. None seem to be able to navigate without a cell phone in hand.

The loudness and total lack of consideration for other users is off the charts

Ever camped near people who have never been outdoors, or have a very shallow history doing it? You can always tell by the loud talking, the lights, music, and hollering. From what I can tell, it’s a combined elation from the new experience and … utter fear. Fear of things lurking in the dark that they think what to eat them. Luckily, I can shed these folk pretty easily, but it’s becoming more and more difficult with the online trip reports, geotags, and so on, that inspire people to go deeper and further, as long as they have the information to get them into the place.

The amount of bodily abuses to places is currently off the charts

I’ve always been observant and angry about people doing the bathroom thing wrong. Sadly, novices and the generally inconsiderate have always been a part of the outdoor landscape, but lately…. Woooo! …. It’s off the charts. It appears that many of the new users think that when the campground overflows, you just go camp wherever you park it and defecate on the ground. And just leave it. Toilet paper strewn in shrubs, trees, and just on the ground … is crazy common. I got a real sense of all of this when my usual outdoor vehicle was under surgery and we did a trip in our more conventional car – we weren’t able to scrape crowds like normal. The things we found in these heavily used places were … unbelievable.

I suppose this all comes down to whether there’s an “outdoors ethic” – maybe something like a land ethic ala Aldo Leopold – but more for outdoor recreation users. It seems that the experienced often know how and why to use places well and treat them with respect. A stereotype that I hope holds up. But if there is, and it’s not some kind of required reading, how do we enforce it?

It appears the answer is that there is no cohesive outdoor ethic, and there is no way to enforce it. Those of us who have centered our lives around being outside of domestic spaces are apparently just going to have to live with it until the newcomers either get tired of it and find another fad/trend to follow, or until they learn to treat the place better.

But the West is really where this appears to be a colossal issue. When the pandemic hit, nobody went flocking to New York City to escape the pandemic … they jetset for Colorado instead. And what that did was to reveal just how much damage all the trip reporting, and apps to help people to find places to recreate, have really done.

I know it sounds like I regard these places as ‘ours’ or ‘mine’, but I assure you, that’s not the case. I regard these places as being a commons that is best left exposed to those who earn their way there – by putting skin in the game to explore these places with respect, and to be part of them in a way that isn’t only for the aesthetic, the newcomer-thrill, or what it does for your social media account and ego. I hope to see people explore in such a way that they’re there authentically, rather than merely to get some adrenaline and some ‘gram imagery. Because those people are never respectful of the place, they never understand it, and they view it as part of their social landscape, rather than as something of inherent value.

I suppose I’m arguing that the explosion of interest in the outdoors as a result of the pandemic was a fire already burning, and that it centered on the West due to the disruption that happened in urban spaces. You’ll notice that nobody went fleeing to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to find a piece of the outdoors. Instead, they went fleeing to Denver, Colorado, or Salt Lake City, Utah, or Phoenix, Arizona. And what they brought with them was a new wave of unacculturated outdoor attitudes, YouTube-trained experience, and pretty much all of the bad things you can associate with city-centered people to our non-domesticated spaces.

Every so often, the YouTube algorithm feeds me some video-log of someone doing some trail in my, or a nearby state. I don’t click on it anymore – and when I do, I find myself enraged and kind of laughing at these people at the same time. The video that triggered today’s entry is one that talked about their “four-wheel-drive expedition in [X] Wilderness area.” Well, funny news, mechanized travel in Wilderness areas is illegal – even on bicycles. It became quickly clear that these urbanites had found their way onto a trail via another trip report or “adventure app”, and did not understand how to read a map – or know that they couldn’t drive their car in a Wilderness area. And, they proceeded to talk about how this area is, “known for being a well kept secret, and is totally off the beaten path.” Ahem, what?!

But that’s exactly what I’m pointing to here – the new public lands user, especially those taking the time and energy to video themselves and publish online, are unskilled, unaware, and do not seem to know much or anything about public lands. And now, thanks to trip reports, GPS points, friends, and so on, they have access to places they never, ever would have found on their own. There’s no skin in the game, no lifetime of study needed, and these same people will spend a lucky day with nobody around and will then advertise the place to the … entire internet. It’s an ethics paradox that I can’t fathom or calculate.

In the end, advances in technology have sealed these outcomes – the exposure of places for consumption and social media likes, over authentic experiences, developing skills to care for and understand the place you’re in, and so on. But that doesn’t mean we have to like it, and it doesn’t mean we have to support it. Unfortunately, since there is no established ethic, and those who acculturated to what was there before are now so diluted by the newcomer-exurbanites, hope for good and careful land use appear to be almost entirely dashed. Especially in the West.

The Fleeting West is written by a rooted and rotten westerner with decades of experience in the outdoors, built on generations of inherited knowledge about the outdoors, watching and writing about the demise of everything held dear.

An old post I know, but consider this an update from the front lines. Just prior to the pandemic, I moved from the “popular” public land management agency to the “big” public LMA and witnessed firsthand the massive increase in free, dispersed camping use. Anecdotal, yes, but the camping areas we manage that lay on the outskirts of NPS units are to this day rife with the scars of the novice user. This last weekend, on a 0900 patrol, I found 5 smoldering fire rings. The ancient PJ forest has been hallwayed by virgin camp saw wielding Sprinter and RTT pilots. This area in particular went from 5 sites to more than 40 over the summer of 2020. And it’s not ever going away. Enjoy your writing, thx!

I grew up in Washington state where we learned at a young age to respect the outdoors and leave no trace. My first backpack was made of wood and rubber inner tubes for support. During my high school years, friends and I covered the Washington Cascade trails where we could pack in for days without seeing anyone. I spent time as a scoutmaster in the Boy Scouts and I introduced my own boys to backpacking and leave no trace before the days of REI. Now iPhone apps list everywhere the "Instagram" crowd goes. No area is unknown anymore. My brothers and I still have our own 'secret' trails and areas we can disappear into, but those are disappearing. As far as I'm concerned, the locusts are ruining the outdoors. I'm ready to hang up my hiking boots and just stay on my property in Western Oregon.